Music is an essential part of all human cultures of all ages. And yet, it does not follow that access to music was equally distributed before the middle of the 20th century. On the contrary, until 1700 (when the first public music concerts were organised in Hamburg and London), music did not play a major role in most people’s lives. This has changed dramatically over the 300 years since then. Few cultural assets are as ubiquitous today as music. Accordingly, the culture of music appreciation, i.e. the sum of all traditions, behaviours, expectations, rules, rituals, devices and equipment associated with music consumption, has changed dramatically since modern times:

I. Listening to music before 1900

Before around 1900, if you wanted to listen to music, you had to learn to play an instrument yourself or be wealthy enough to pay someone else to do so (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 – Abraham Bosse – Music Society

Since the Middle Ages, it has been part of every proper education for a young person to learn to play a musical instrument. This practice was adopted in the education of aristocratic offspring – and later, with the rise of the bourgeoisie, also by middle-class families who endeavoured to imitate their aristocratic role models. From the 19th century onwards, this practice shifted more towards the musical education of female offspring, as it was expected to be conducive to finding eligible husbands.

Until around 1660, self-determined listening to music was primarily the preserve of wealthy – mostly aristocratic – households, who employed professional musicians, initially travelling musicians, for their evening entertainment or festive occasions (banquetts, weddings, funerals etc.), and later employed them permanently in their large households (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2 – Adolph Menzel – Frederick the Great Playing the Flute at Sanssouci, 1852

For example:

- the Electors of Saxony maintained a court orchestra of over 50 musicians, led by such outstanding personalities as Heinrich Schütz, Johann Heinichen, Jan Zelenka, Johann A. Hasse and Carl Maria von Weber. The former court orchestra, now the Saxon State Orchestra, has been at the forefront of the music industry for almost 500 years without interruption: from its foundation by Moritz von Sachsen in 1548 to the present day.

- the Princes Esterhazy maintained a 20-piece court orchestra (founded around 1664) with such illustrous composers as Haydn and Hummel among others at ist helm.

- from 1720, the Electors of the Palatinate created one of the most influential orchestras in music history with the Mannheim Court Orchestra, which consisted of over 40 musicians and included such important personalities as Johann Stamitz, Georg Joseph Vogler and Franz Xaver Richter.

Most of today’s leading orchestras, such as the Vienna Philharmonic (founded in 1842), the Berlin Philharmonic (founded in 1882), the New York Philharmonic (founded in 1842), the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (founded in 1891), the Boston Symphony Orchestra (founded in 1881) and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (founded in 1888) are all self-governing organisations of bourgoise origin, stemming from a wave of foundations in the second half of the 19th century.

However, the majority of people before 1900 could only enjoy music controlled by others, at certain festivities, mostly in a public setting (e.g. as church music during high mass or as dance music at funfairs etc. ) or had to employ someone else to play for them or had to play it themselves (Fig. 3):

Abb. 3 – Abraham Teniers – Funfair, 1646

From around 1600 and the rise of the middle classes, an important branch of music production emerged for skilled amateurs who practised music at home with their families. The majority of the chamber music oeuvre of all composers was aimed at this clientele. Publishers such as John Walsh in London (Händel) or Estienne Roger in Amsterdam (Corelli, Vivaldi) or Le Cène (Geminiani, Locatelli) were global corporations in their day (18th c.), which lived primarily from this mostly middle-class clientele. Some of the publications also had an explicitly educational character and bore titles such as ‘L‘Arte del violino’ (Locatelli, 1733) or ‘Der getreue Music-Meister’ (Telemann, 1728) (Fig. 4), the latter of which Telemann business-mindedly offered as a subscription – with instalments every fortnight:

Abb. 4 – Frontispiece, G. Ph. Telemann „Der getreue Music-Meister“, 1728

or the ‘Clavierübungen’ by Johann S. Bach in four parts (published 1731 – 1741; ‘Denen Liebhabern zur Gemüths-Ergetzung verfertigt’) or ‘Notenbüchlein für Anna Magdalena Bach’ (Bach, 1725), more for personal domestic use, and later, for example, the Schubertiades of the early 19th century. This was followed by publications with the addition ‘arranged for easy playing … ’ on the front cover – from the 19th century also for keyboard instruments.

With the growing interest of an increasingly educated middle class, bourgeois music societies (Collegia Musica) with regular public concerts began to emerge in the late 17th century. The first public concert of a Collegium Musicum took place in Hamburg in 1660 under the direction of Matthias Weckmann – still free of charge. The first public concert for an entrance fee was organised by John Banister in London in 1672. While public music performances without dancing had previously been generally associated with a religious or courtly context – liturgy, ceremony or banquet – they were now – for the first time – understood as an artistic exercise in its own right. Music emancipated itself as an art form (!). In 1710, the first public concert organisation, the Academy of Ancient Music (1710-92), opened in London, followed by the concert series organised by Telemann in Frankfurt am Main in 1713 and in Hamburg in 1723. At the same time, the Collegium Musicum, founded by Telemann in Leipzig in 1701 and directed by Georg B. Schott from 1720, began its famous co-operation with the Café Zimmermann, which was subsequently directed by Johann S. Bach from 1729-41. There were also the Concerts spirituels in Paris (1725-91) and the first subscription-based concerts, the so-called Bach-Abel concerts in London (1765-82).

A compromise for people who were either unable or unwilling to learn to play an instrument but did not want to do without music in their own four walls was provided by wind-up mechanical music boxes, which were produced from the 16th century onwards primarily for middle-class customers (from around 1796 as music boxes also in clocks). They initially played on pipes or musical combs (Fig. 5):

Abb. 5 – Cylinder musical box by Nicole Frére, ca. 1850

The corresponding music data carriers were usually in either cylindrical or disc form – later in paper form – and were exchangeable on the machines. Remarkably, these data carriers are digital! Take a closer look at such a cylinder. The music is fixed in a code (per tooth) that defines its information from only 2 states: ‘pin’ and ‘no pin’, i.e. ‘1’ or ‘0’, ‘on’ or ‘off’.

Music consumption remained essentially the in this fashion until the end of the 19th century. The simple music automatons, which became widespread from 1800 onwards, did not yet noticeably change the culture of listening to music. Their repertoire was quite limited and their timbre could convey little emotionality. If you wanted to listen to ‘real’ music, you still had to play it yourself or pay others to do so. For the latter, a rich commercial concert and opera life had developed in all European metropolises from around 1700, in which large sections of society could already participate. But from the late 19th century onwards, machines appeared that made ‘real’ music at home without the household members having to practise and play musical instruments themselves. Not surprisingly, with the advent of these devices, the culture of domestic music making came to an end after 300 years.

While the first automatic musical instruments were still small table-top devices driven by wind-up mechnanisms, they became larger and larger over time (e.g. fairground organs) and eventually developed into highly complex automatons that could play entire ‘bands’ consisting of piano, violins, pipes and percussion, later even with the help of electric motors. In addition to cylinders or discs, their music data carriers were perforated paper strips (‘orchestrion’ or ‘polyphon’ Fig. 6):

Fig. 6 – Orchestrion „Violano Virtuosa“, by Mills Novelty, ca. 1900

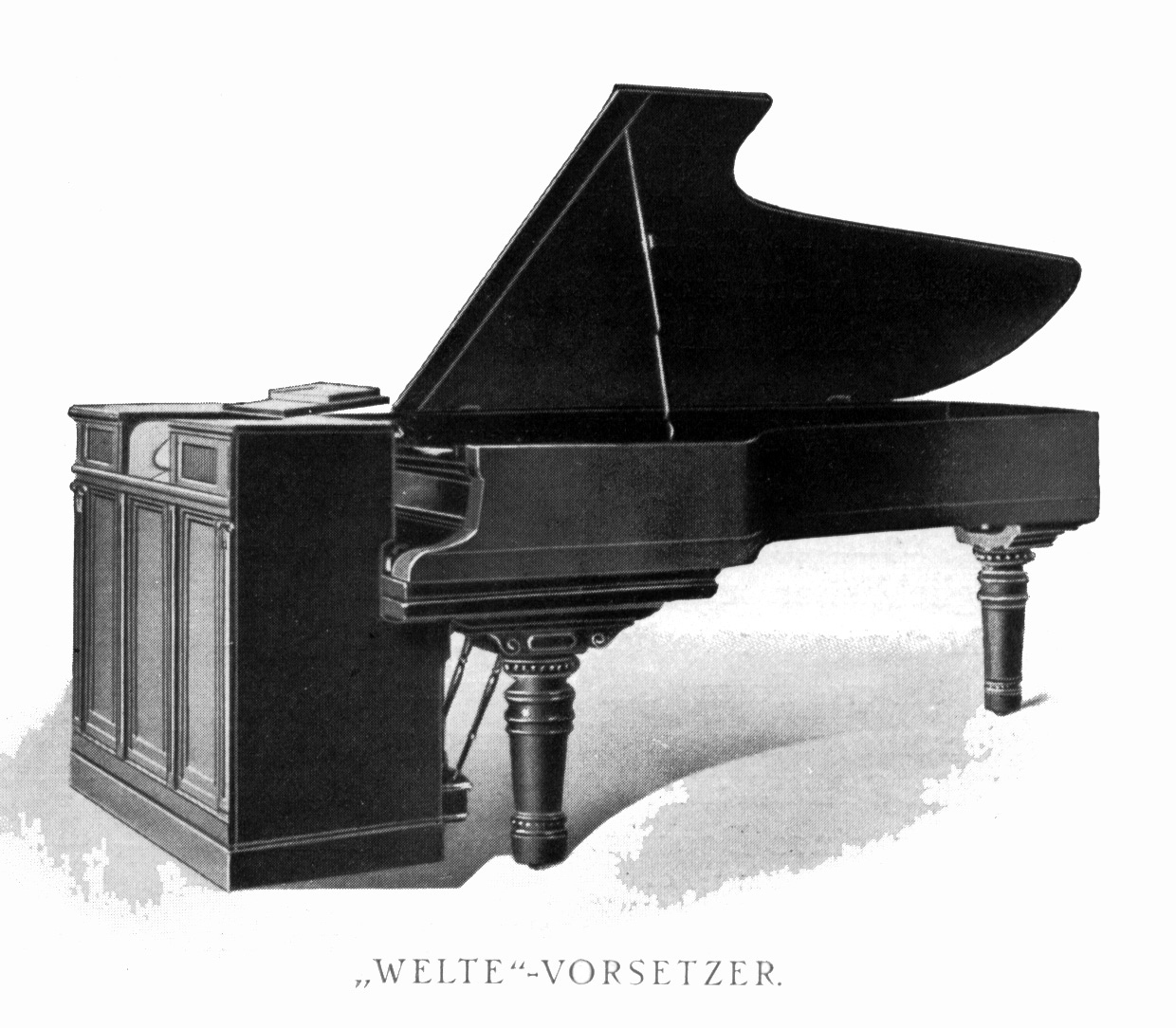

A first highlight from a musical and audiophile point of view was the Welte-Mignon reproduction piano from the company M. Welte & Söhne in Freiburg, whose technology was patented in 1905 (Fig. 7):

Fig. 7 – Player piano by Welte-Mignon, 1906

It used perforated paper rolls with 100 control strips as data carriers. Whereas player pianos by other manufacturers, like the Aeolian Company could just record und reproduce the notes, the Welte system made it possible to record and reproduce piano performances with a high degree of authenticity in all delicate details of keystroke, dynamics, agogics and pedalling. These recordings are still spectacular and of breathtaking quality even today. Everyone who was anyone in the piano world around 1900 came to one of Welte’s two recording studios in Freiburg or Leipzig to record their art for posterity; for example the composers Claude Debussy, Camille Saint-Saëns, Alexander Scriabin, Max Reger, Edvard Grieg, Enrique Granados, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss and George Gershwin or the pianists Carl Reinecke, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Ferruccio Busoni, Artur Schnabel, Edwin Fischer, Walter Gieseking, Vladimir Horowitz and Rudolf Serkin.

However, the Welte-Mignon system or the orchestrions and polyphones were the preserve of the very rich or of hotel and shipping line companies. They simply cost a fortune.

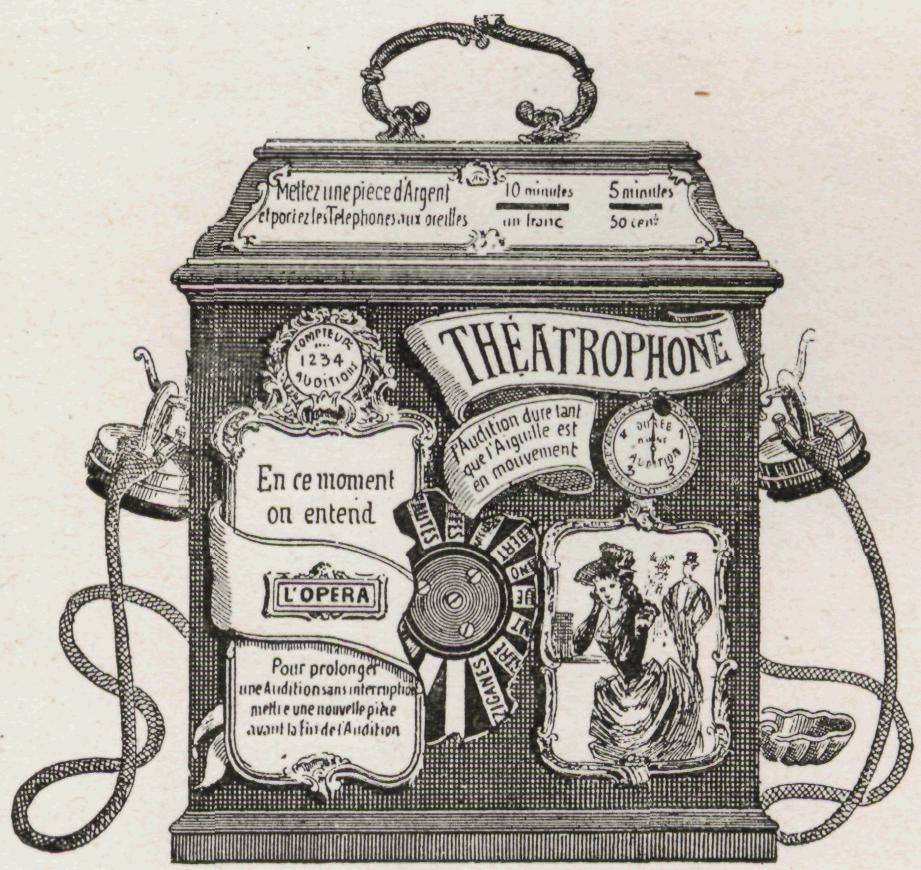

Considerably cheaper were the so-called ‘Théatrophones’ from French aviation pioneer and inventor Clément Ader (Fig. 8), but less ‘audiophile’. Ader had worked on the further development of Alexander G. Bell’s telephone system and set up his own telephone network in Paris around 1880. During the International Electrical Exhibition in Paris in 1881, he used his telephone network to transmit opera performances (in stereo!) electrically from the Opéra Garnier to a room 2 kilometres away in the Palais de l’Industrie on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, where these signals could be listened to by opera lovers via two telephone receivers. The International Electrical Exhibition in Vienna in 1883 also presented the transmission of performances from the Vienna State Opera using Ader’s théatrophones. The théatrophone was operated commercially in Paris from 1890 to 1932 with coin-operated machines (10 minutes for 1 franc, 5 minutes for 50 cents), whereby the programme range was extended to include the transmission of church services and the reading of current news. In terms of both content and technology, the Théatrophone was thus a direct forerunner of the radio and of streaming.

Fig. 8 – Coin Theatropone, ca. 1881

II. Listening to Music since 1900

Until 1900, all musical events were completely ephemeral, one-off, irretrievable events. Even the concerts of the greatest artists up to around 1900 could only be enjoyed by those present at the concert and only during the concert. After the concert, the artistic achievement was lost forever – all that remained was the memory of those who were there. From around 1900, mankind succeeded in capturing sounds, preserving them and ‘reproducing’ them on demand. Music was played back at home as we know it today – with more or less affordable devices – first wax cylinders, then shellac later vinyl records, radio, tape and finally CDs and streaming. Due to the enormous dissemination of these devices, music is no longer experienced ‘live’ by most people since around 1900, but predominantly via devices. Sound carriers and technology have therefore become central to the listening experience and the culture of listening to music. And it is this technical aspect that we want to focus on in the following.

It all started rather small: In 1877, as a by-product of his research into telecommunications, Th. A. Edison developed a wax cylinder-based recording and playback device with a vertically cut groove, the phonograph (Fig. 9). It was actually designed for dictation purposes in the office. After the device was completed, after much trial and error on 6 December 1877, the first recording was made by Edison saying ‘hello’ into the funnel and then ‘hello’ again. He then sang the English nursery ryhm ‘Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow, and everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go’, which he played to his colleagues after the recording. Edison was not the first person to make a sound recording. That honour goes to the French printer, bookseller and inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville and the ‘phonautograph’ he developed. Although the phonautograph could record sounds, it could not reproduce them. Edison’s phonograph, on the other hand, could record and reproduce sounds, making Edison the first person to hear his own voice on a recording.

Fig. 9 – Edison Phonograph, ca. 1900

This idea was taken up by Emil Berliner and he developed a disc-based recording and playback system with lateral writing in a spiral groove, which he called the ‘gramophone’. He applied for a patent for it in 1887 (Fig. 10). The gramophone disc was born!

Fig. 10 – Gramophone Victor III by the Victor Talking Machine Co., ca. 1910

The problems of early cylinder and disc systems, such as poor sound quality, short playing time, lack of duplication options, etc., were gradually improved, so that from 1895 shellac records with a diameter of 25cm and a rotation speed of 78rpm were commercially available – from 1904 also recorded on both sides. However, this meant that the recording option of the earlier systems had to be droped. The discs were prerecorded and could only be played back. As shellac discs contain approx. 70% rock powder (and approx. 30% shellac with additives), they were harder than the steel from which the playback needles were made, with the result that the needle ground into the groove profile and scratched into the groove base within a few minutes during playback of one side of a record, so that the needles had to be changed after each side of the record.

As Berliner’s system achieved a much higher sound fidelity than Edison’s phonographs, Berliner focussed his invention on the entertainment industry. To this end, he founded several companies that controlled the entire value chain of music production – from recording and record production to the manufacture and distribution of disc players:

- In 1898, he founded the Gramophone Company in London and New York, which, among other things, became the parent company of ‘His Master’s Voice’ and later developed into EMI in England and, after merging with the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1931, into Columbia Records in the USA.

- Also in 1898, together with his brother Josef, he founded the ‘Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft’, which still exists today.

- In 1901, together with Eldridge R. Johnson, he founded the ‘Victor Talking Machine Company’, which was taken over by the Radio Cooperation of America in 1929 and developed into RCA Victor.

From August 1898, the first European recordings were made in the basement of the Gramophone Company’s headquarters at 31 Maiden Lane in London under Berliner‘s assistant Fred Gaisberg. Although the early recording technology could only capture a limited sonic range, the company endeavoured to cover as broad a musical spectrum as possible. Shorter classical pieces and opera arias were just as much a part of the catalogue as popular dance music and the latest operetta melodies. Soon the producers began to look for the best interpreters for record productions throughout Europe.

In July 1900, Emil Berliner registered the painting by the American painter Francis Barraud with the longing dog Nipper as the trademark of his Gramophone Company. ‘His Master’s Voice’ was born and Nipper still watches over the sound quality of the EMI company today.

From 1910 onwards, gramophones and music on discs finally became a mass phenomenon (Fig. 11):

Fig. 11 – HMV London Store, Oxford St., 1920s

The first stars of the young record industry were Enrico Caruso (1873-1921) (Fig. 12), who was employed by Berliner’s London Gramophone Company from 1902 onwards:

Fig. 12 – Enrico Caruso with Phonograph Victrola, ca. 1918

and Louis Armstrong (1901 – 1971) with his Hot Five (Fig. 13), who was engaged with Berliner’s Victor Talking Machine Company in the USA since the takeover of Okeh-Records in 1926:

Fig. 13 – Louis Armstrong & the Hot Five, ca. 1926

The English-American conductor Leopold Stokowsi (1882 – 1977) was probably the most enduring artist in the history of recording (Fig. 14):

Fig. 14 – Leopold Stokowski at Carnegie Hall, 1947

Between 1917 and 1973, he made over 700 recordings and influenced technical developments in stereophony and long-playing disc recordings, among other things. Stokowski made his first disc recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra for the Victor Talking Machine Company in October 1917 (Brahms Hungarian Dances) and his last recording in 1973, at the age of 91, with the International Festival Orchestra for Cameo Classics (Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony). This makes Stokowski the artist with the most recordings in recording history (probably followed by Nana Mouskouri – if you ignore Ashla Bhosle and Lata Mangeshkar, who are said to have made up to 11,000 recordings each as backing singers for Bollywood productions).

In the USA alone, annual record sales reached 150 million units in 1920. The grammophone record was the dominant audio format and would remain so for most of the 20th century – until its sales were overtaken by the compact cassette in 1983 and the compact disc in 1989 (both of which it – ironically – overtook again subsequently).

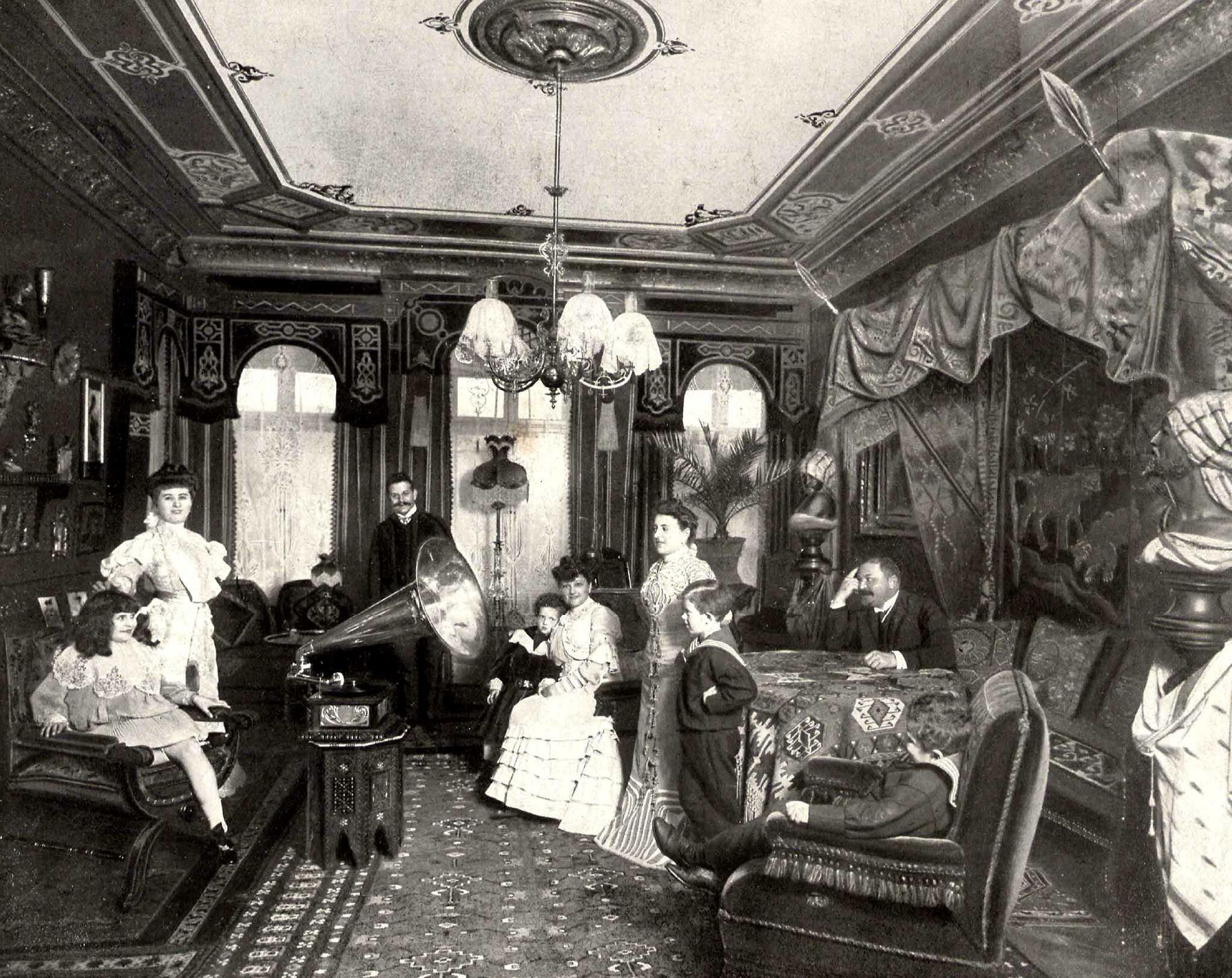

From 1910 onwards, a device for playing music was a standard element of any upscale middle-class living culture (Fig. 15):

Fig. 15 – Upper middle class household in Berlin, ca. 1910

From around 1920, radios were added and temporarily threatened the rise of gramophones. Customers could choose between stand-alone gramophones (Fig. 16)

AFig. 16 – His Master’s Voice Grammophone, ca. 1928 (© Sammlung Dirk Naumann)

and stand-alone radios (Fig. 17):

Fig. 17 – RCA Superette R8, ca. 1930

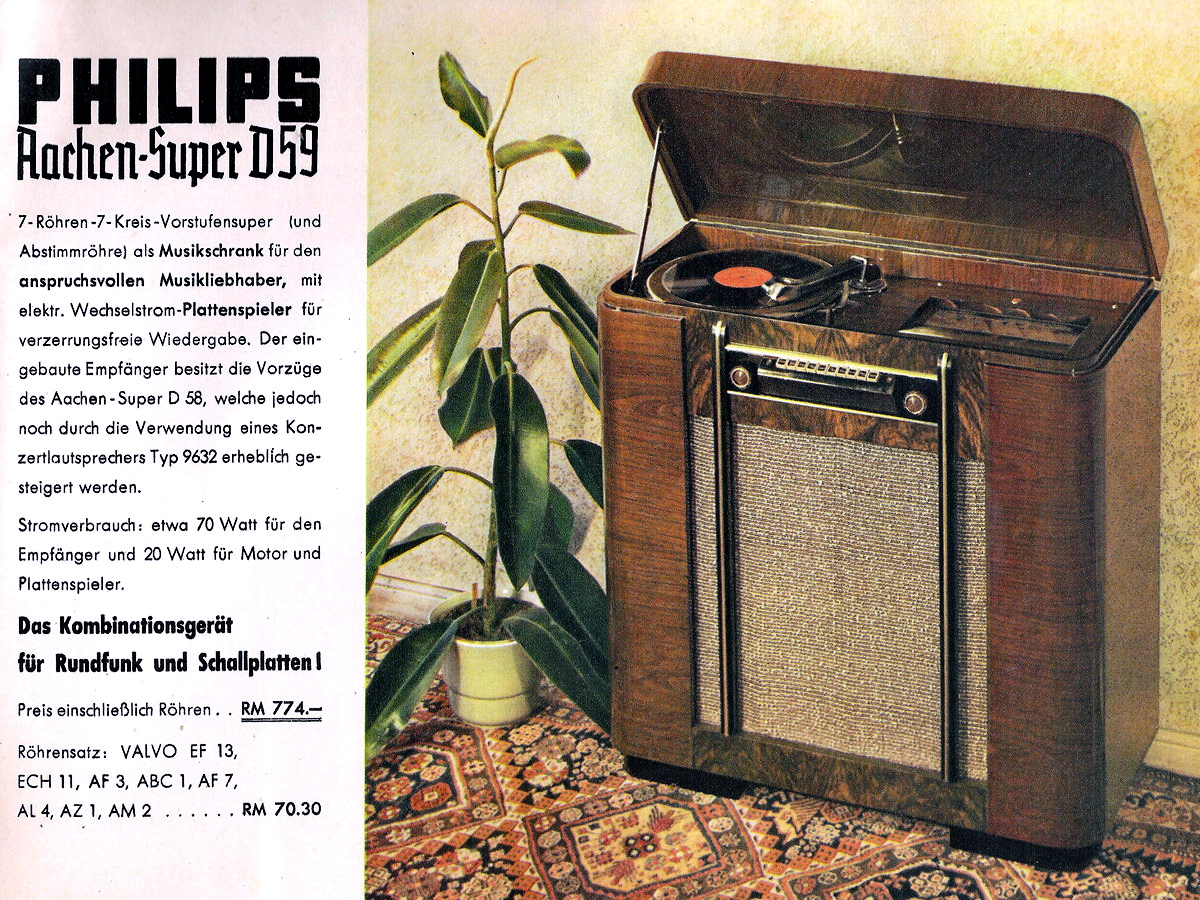

and combined devices from the 1930ies onwards (Fig. 18):

Fig. 18 – Philips Aachen Super D59, 1940s

The devices were designed to integrate more or less seamlessly into existing contemporary living room fashions (music boxes that looked like chests of drawers or sideboards) (Fig. 19 & 20):

Fig. 19 & 20 – Music box Grundig 1260W, 1950

From the outset, customer requirements and therefore the manufacturers’ marketing messages focussed on three areas: Sound quality, design and user-friendliness. At the same time, there has been a trend towards mobility since the 1920s. To this day, these four factors – depending on current fashion, personal preferences and area of use – determine consumers’ purchasing decisions in varying order.

The term ‘HiFi’ as an abbreviation for ‘High Fidelity’ was probably coined by the British sound engineer and loudspeaker developer H.A. Hartley: „I invented the phrase „high fidelity“ in 1927 to denote a type of sound reproduction that might be taken rather seriously by a music lover.”

Despite many improvements, the running time of records was still only around 4-6 minutes per side until the end of the 1920s. As a solution for musical works that lasted longer – especially works of classical literature – several shellac discs were bound together to form an ‘album’. RCA Victor Co experimented with reducing the rotation speed to 33 1/3 rpm in order to extend the playing time and on September 17, 1931 presented the first ‘long-playing record’ where an entire album fitted on one disc: Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, played by the Philadephia Symphony Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski, on a disc with 2x 16 minutes.

On June 21, 1948, Columbia Broadcasting Systems Inc. (CBS) finally introduced the polyvinyl chloride (vinyl) long-playing record (LP) developed by the Hungarian-American physicist Peter Carl Goldmark with a microgroove and a playing time of 23 minutes per side. Vinyl records could be produced more cheaply and in better quality and they were less fragile than shellac records and hence, became established in Europe and North-America from the mid-1950s (shellac records were still being produced in Asia and South America until the late 1960s).

From the mid-1950s – after a severe slump in the global music market in the wake of the Second World War and the resulting shortage of materials (e.g. shellac) – the music industry experienced an extraordinary boom. In the wake of the economic miracle, music consoles became a status symbol for the living room from the 1960s – just like the car on the doorstep.

In the mid 1950s, recording technology developed towards 2- respectively 3-track recordings, with the result that from the beginning of the 1960s, consumers added a second loudspeaker to the first and music consoles increasingly developed into living room altars (Fig. 21):

Fig. 21 – Braun RS10 W Stereo, 1961

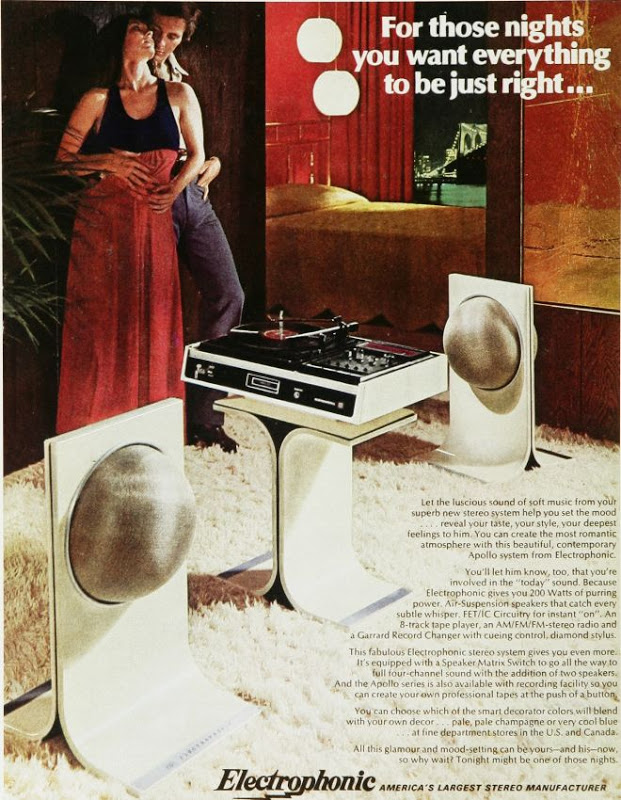

From the 1960s onwards, consumers’ demands on their music playback devices began to diverge: some placed greater emphasis on integrating music devices into the living environment, in the form of increasingly complex music consoles that also adapted to unusual interior design styles (Fig. 22 & 23):

Fig. 22 – General Electric – Scandia, 1968

Fig. 23 – Electrophonic Apollo System, ca. 1975

They were mostly designed as compact systems or top loaders (flat and operated from above, like a control desk).

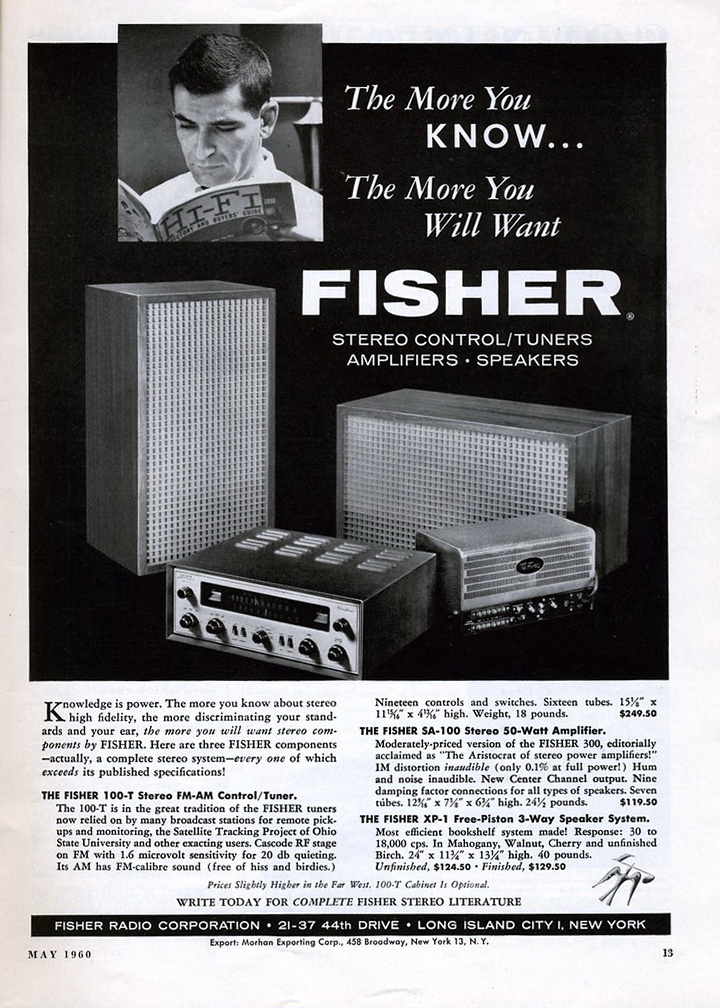

The others attached greater importance to the highest quality of music reproduction and therefore accepted devices that could not deny their technical character, in the form of semi-professional individual devices with a studio flair (Fig. 24):

Fig. 24 – Fisher Stereo System, May 1960

Not least, the superpowers’ race into space, which was conducted with much media presence from the 1960s onwards, led to an increased interest in science and technology among the general public, as well as a desire to own a piece of high technology at home. The hi-fi system thus became a symbol of the owner’s modernist status.

Later, in the 70s, classic hi-fi racks appeared, such as a studio technology tower with a record player on top, which only Dad was allowed to operate (Fig. 25). Everyone else had to sit reverently in front of it and listen. Even the loudspeakers looked like studio monitors. Perhaps you still remember?

Fig. 25 – Pioneer Rack

From the 1970s, a compact cassette player was added to the record player and tuner, and later, from the early 1980s, a CD player. In return the 8-band equaliser and the reel-to-reel tape machine disappeared (Fig. 26).

The compact cassette had a slow start. Although it was introduced by Philips on August 28, 1963 at the 23rd Große Deutsche Funk-Ausstellung in Berlin, it took another 8 years before it was accepted in hi-fi circles with the 201 Tape Deck from Advent in 1971. It took various improvements in tape types (coating with chromium dioxide from 1971 and pure iron/metal from 1978) and noise reduction (Dolby-B from 1968) to bring it to an acceptable performance level. The cassette maschines brought customers more fun through interaction, as the hi-fi disciples could now feel like little sound engineers. The compact cassette recorders introduced two developments that were to become groundbreaking for the way music was consumed in the 21st century:

- With the possibility of recording, the general public could at last create their own music programmes. Although this had been technically possible before with reel-to-reel tape machines and 8-track tapes, these were not widely used due to their high price and inconvenience of operation.

- The compact size of the compact cassette made real mobile devices possible for the first time.

The success of the compact cassette was so resounding that from 1983 sales of pre-recorded compact cassettes outstripped those of vinyl records.

Fig. 26 – Braun Rack – Atelier Series, 1983

Feedback from the culture of listening to music to the culture of making music

In this context, it should not go unmentioned that the technology of sound recording has not only fundamentally changed the culture of music listening on the part of consumers, but also the interpretative practice of musicians. The mere fact that the interpretation, as soon as it is fixed in a recording, loses its spatio-temporal context and the unreproducability anchored in it, has consequences for the performer’s approach to the work. In addition, the absence of the audience in the recording studio focusses the performer on himself and the interaction with a team of technicians and the producer. Two contrasting examples of the influence of recording technology on the performer are Sergiu Celebidache and Glenn Gould. While the former vehemently rejected studio recordings because he understood the transience and unreproducability as an elementary component of music-making, the latter completely renounced live concerts from 1964 onwards in order to work on his sound ideal, which he believed he could only realize in the studio.

The ability to produce perfect and flawless music in several ‘takes’ in the studio (10-15 takes per recording are common in classical music production) in turn becomes the benchmark for the expectations of the audience in live concert situations. Time and again, performers report the difficulties of doing justice to their own recordings in performance practice. Even a conductor as eminent as Georg Solti failed in 1983 in Bayreuth to live up to his benchmark recording of Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen for the British Decca label, which had been supervised by John Culshaw. In addition, the availability of interpretations categorised as ‘references’ has led to a harmonisation of the interpretation of works across national and academic boundaries. In the past, a Russian singer or pianist sounded fundamentally different from a German or French one. Today, they all sound pretty similar – even if at a high performance level.

In order for the recording to sound ‘good’ at home in one’s own four walls via two more-or-less point source loudspeakers, it must be adapted to this by the recording engineers during the recording process (sound design). It is a misconception to assume that any good-sounding recording will reproduce the actual conditions in the studio or concert hall neutrally – even from an ideal sound perspective (such as the conductor’s podium). The assumption that the task of the recording technicians is limited to a faithful reproduction of the interpretation is based on a misunderstanding that the record companies have done their utmost to nurture as part of their marketing strategies. The microphone is not a technical substitute for the human ear, the living room is not a concert hall and the loudspeaker as a point source of sound cannot be compared in the slightest with the complex resonance conditions of a musical instrument or even an entire ensemble in a concert hall. Any attempt to reconstruct a sound impression that is assumed to be ideal in the concert hall under domestic conditions inevitably involves extensive technical intervention in the sound and thus in the interpretation. Recording technology has thereby taken over a not inconsiderable part of the interpretation of the work. The most famous example of this may be DECCA’s Wagner Ring by legendary producer John Culshaw, in which he used recording technology (‘SonicStage’) to reproduce the stage drama in all its details and spatial relationships much more authentically than one would normally see and hear live in an opera performance. This realisation led to many successful conductors in the recording age taking an intensive interest in the details of recording technology, microphoning and mixing, such as Leopold Stokowski and Herbert von Karajan. Stokowski, for example, vehemently claimed control over the technical realisation of his sound concept (‘No one controls Stokowski’s sounds but Stokowski’). A control panel was specially built for him and placed next to the conductor’s podium in order to defuse the constant conflicts with the recording technicians.

These influences on the interpretation of classical works, which first emerged through recording technology, raise fundamental questions about the much-vaunted concept of ‘original sound’. The modern culture of recording and listening to music has added a technical sound aspect to classical works that – despite all efforts for historically informed performance practices – they could not have had at the time of their creation.

How did people listen to music at home with their playback devices?

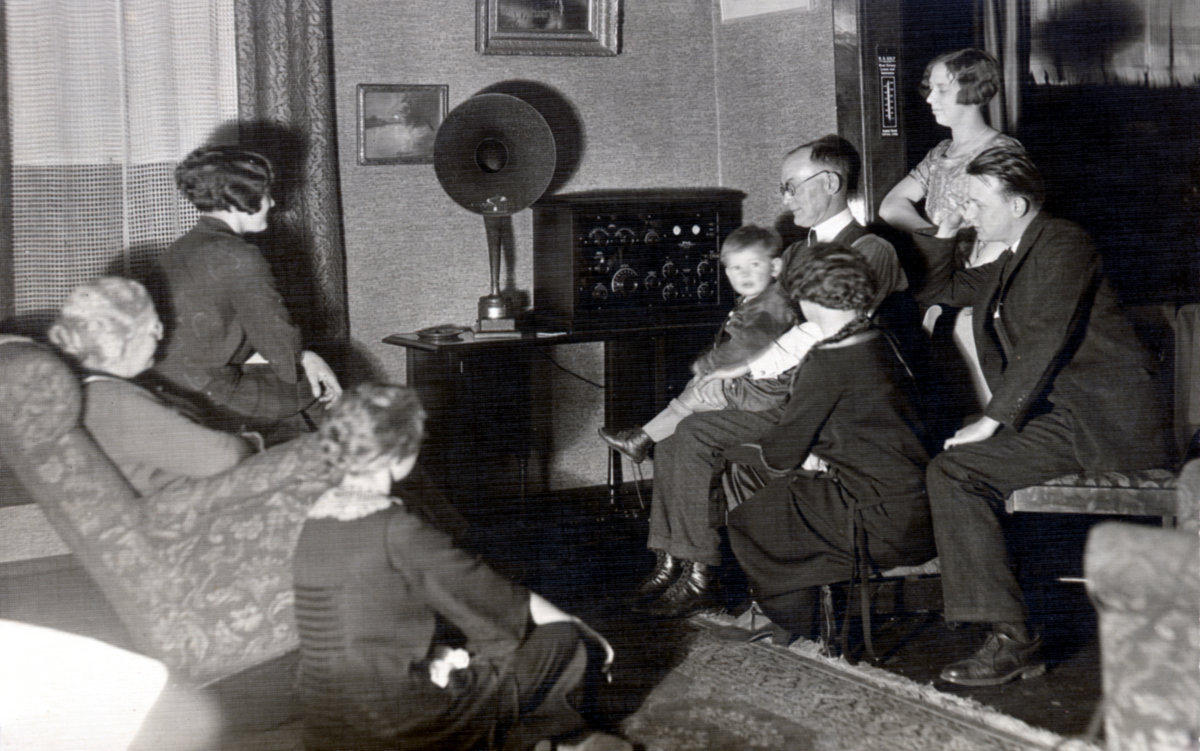

In the beginning, listening to music was a communal event in which the whole family took part. People gathered around the playback device and shared important music broadcasts from the radio as well as the daily news or new acquisitions on record (Fig. 27 & 28):

Fig. 27 & 28 – Families in front f the radio, early 1930ies & 1940ies

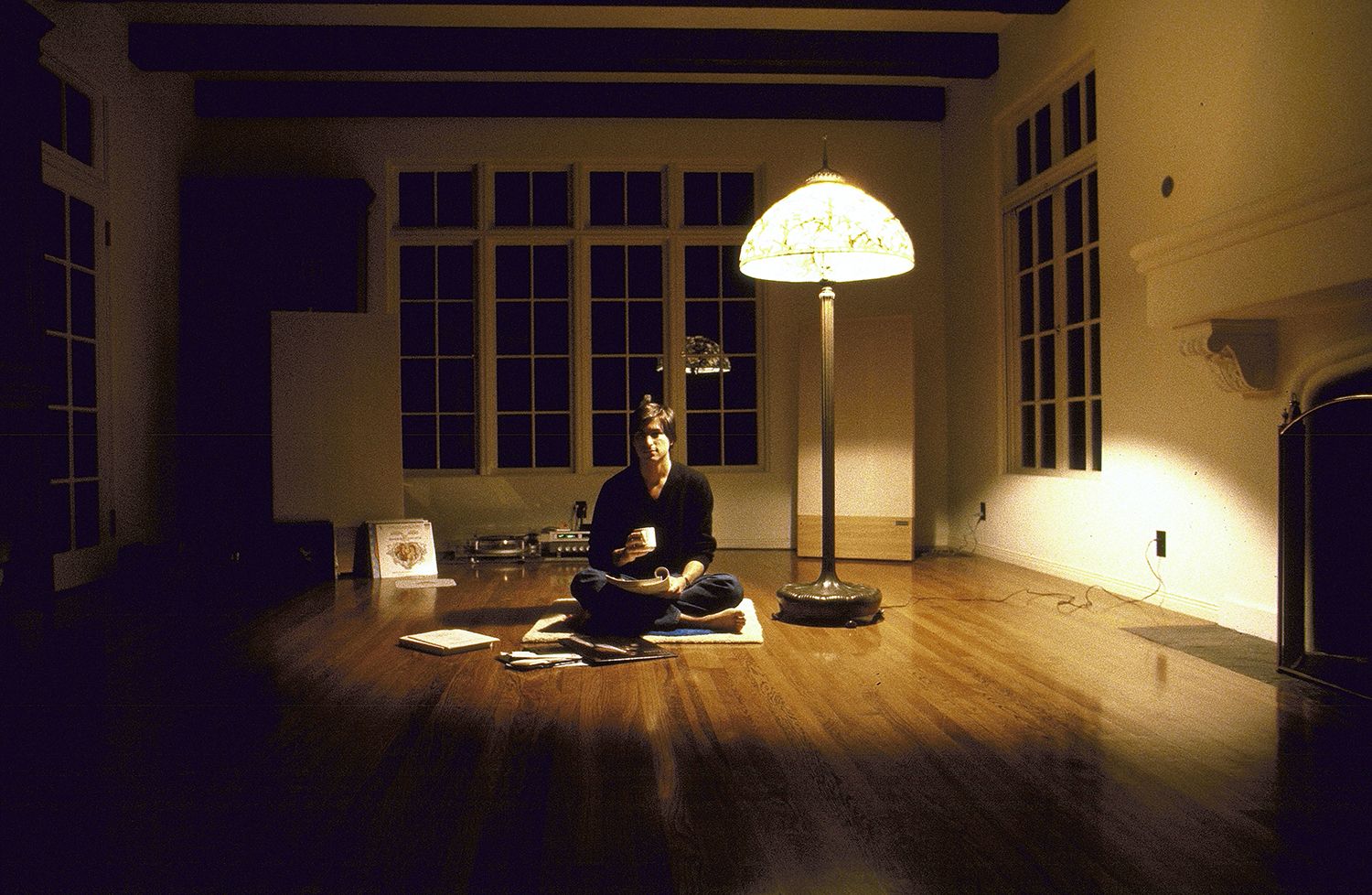

Later, from the 1960s onwards, listening to music became more of a solitary, primarily male domain. Due to the advent of stereophony, the listener now sat alone at a certain distance in the middle front of two speakers. The hard-working man of the late 20th century sought distraction and relaxation with his hi-fi system – a kind of emotional escapism (Fig. 29 & Fig. 30):

Fig. 29 – Frank Sinatra in his ouse in Palms Spring, 1963 with Ampex reel-to-reel machine and McIntosh amplifier

Fig. 30 – Steve Jobs in his Woodside home in California, 1982 – very Zen with a super exclusive stereo

For the aficionados: Steve Jobs had himself photographed for Time magazine by Diana Walker with his carefully assembled stereo system, consisting of: Turntable: Michell MK1 GyroDec, speakers: Acoustat Monitor 3s, preamplifier: Threshold FET-One, power amplifiers: Threshold STASIS-1 and a stray tuner: Denon TU-750s.

Why women have left music consumption behind remains an eternal mystery. Perhaps because from the 60s onwards, stereo systems evolved from music furniture (furnishings – women’s domain) to studio technical devices (technology – men’s domain)?

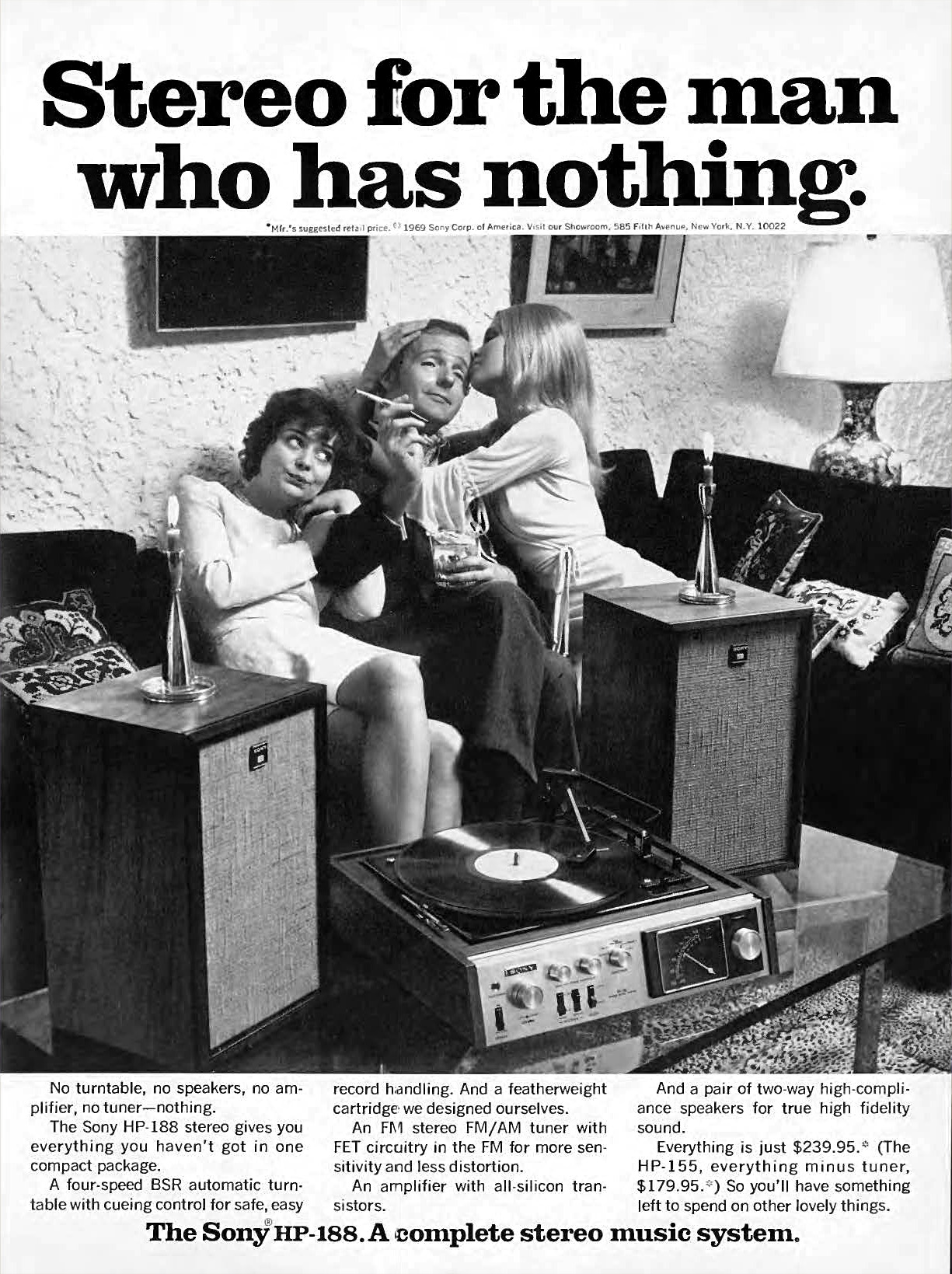

The focus oft he hifi manufacturers on a primarily male clientele was partly softened by the fact that industry advertising tried to suggest to the classic hi-fi bachelor of the 70s that a proper hi-fi system was conducive to attracting female mates (Fig. 31 & 32):

Fig. 31 – Sony HP-188 advertising, Playboy Magazine, September 1970

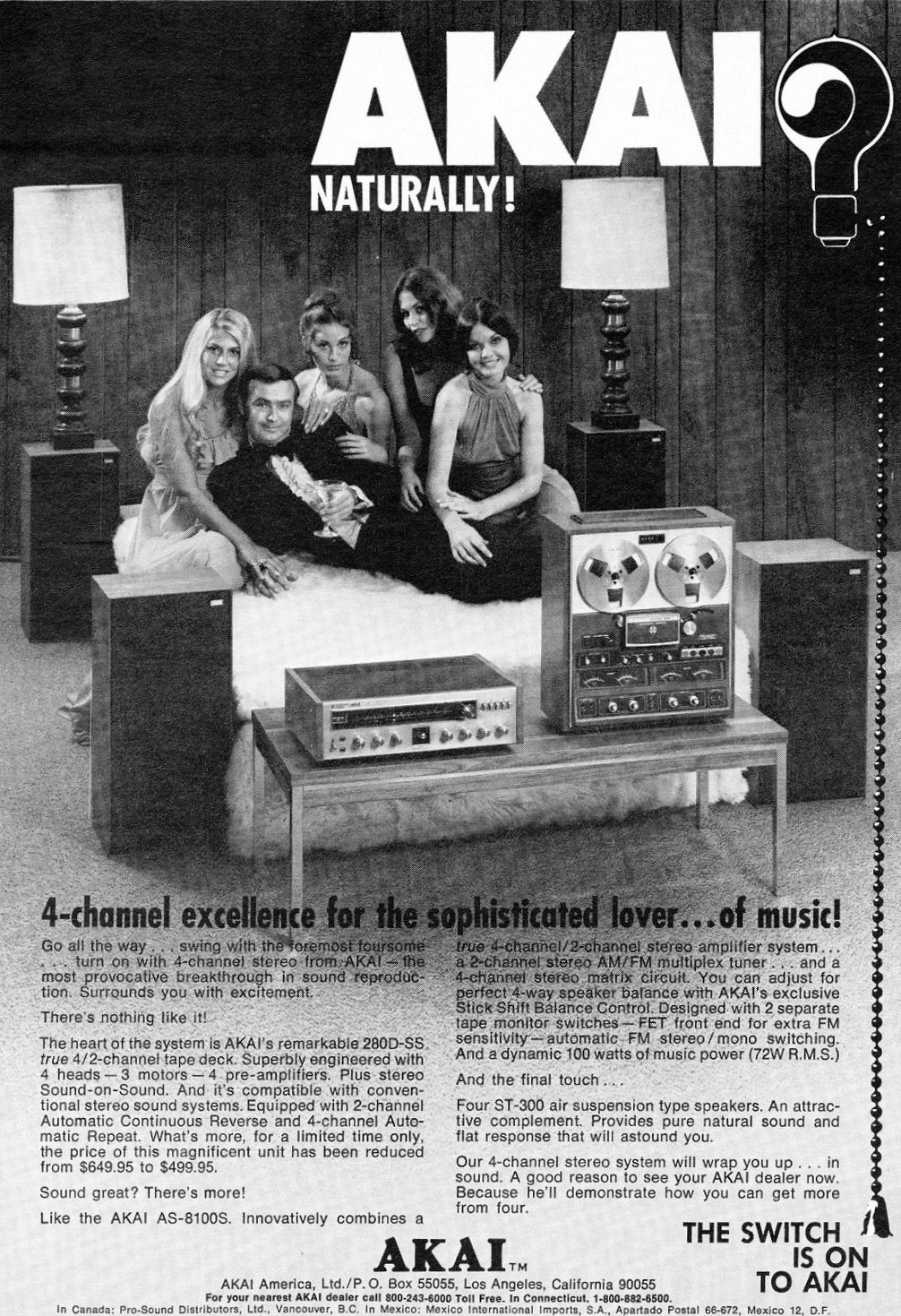

… and what works well in stereo should work even better in quadro … shouldn’t it?

Fig. 32 –Akai Quadrophonic system, AKAI 280D-SS, AKAI AS-8100S and AKAI ST-300, 1975

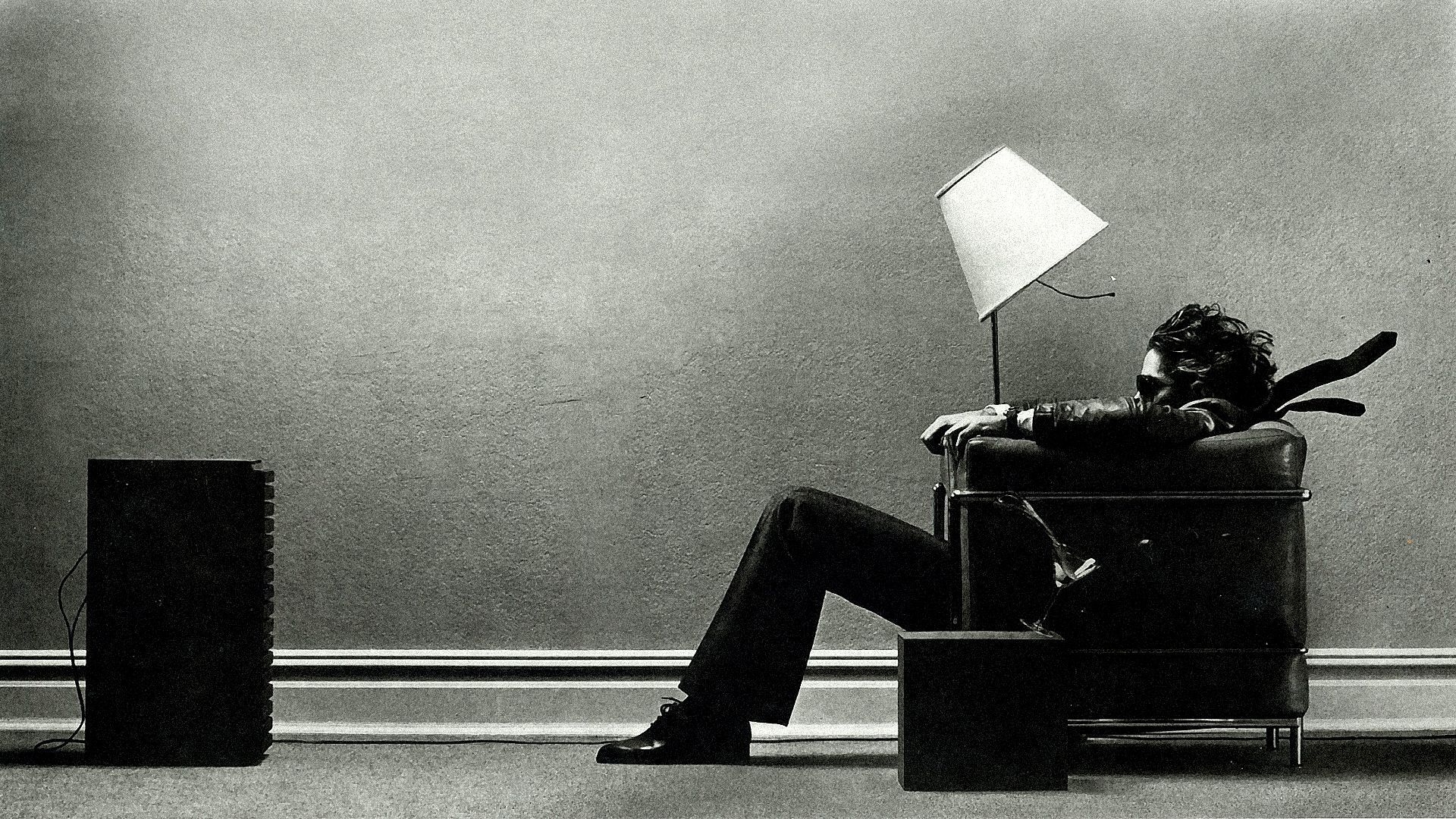

… and if that didn’t work out with the mating partners, the classic hi-fi bachelor could still ‘go full throttle’ with his system and indulge in his escapism all by himself (Fig. 33):

Fig. 33 – ‘Blown Away’ Maxell advertising with JBL L100 by Steve Steigman, 1978

This remained more or less the case until the end of the 20th century. By the end of the century, classic hi-fi had died out: The big names: Marantz, Fisher, Sansui, Denon, Kenwood, Sony, Luxman, Onkyo, Pioneer, Technics but also in German-speaking countries: Braun, Dual, Thorens, Saba, Wega, Grundig, Nordmende went bankrupt, were sold or turned to more promising business areas such as TV/video or mobile consumer electronics. The downfall did not come overnight: the decline began as early as the late 1980s: the major hi-fi manufacturers – in an effort to adapt to suspected changing customer demands – increasingly focussed on integrated systems, midi components and lo-fi, low-budget products with double cassette decks and super bass boosters. These looked as cheap in their plastic casing as they sounded and were not helpful to save the companies. For some reason, the major hi-fi manufacturers of the 20th century had not found the right answers to the changing customer needs at the turn of the millennium.

III. Brave new world – listening to music since 2000

What had happened? Things naturally get a bit murky from here on, but basically five technical developments revolutionised the way people consume music from the end of the 20th century onwards:

1. Mobility of playback devices: Music playback became mobile early on so that people could also listen to music outside of their home:

- The first mobile portable gramophone came out in 1913 (Decca Portable by Barnett Samuel & Co.),

- from the 1920s onwards, there were various attempts to install tube radios in cars. The first commercial car radio was installed in 1924 in New South Wales, Australia, by the Kelly Motors company in a ‘Summit’ model,

but all these devices were still tied to relatively large hardware and had limited mobility. The breakthrough in mobility came in 1979 with Sony’s Walkman (Fig. 34) – and at a teenager-friendly price to boot. Music became available to (almost) everyone, practically everywhere and at all times. From then on, millions of primarily young people encapsulated themselves from their environment with two foam-covered earpads:

Fig. 34 – Sony Walkman Cassette, 1979

On top of that, it was already possible to personalise the music programme with self-compiled compact cassettes.

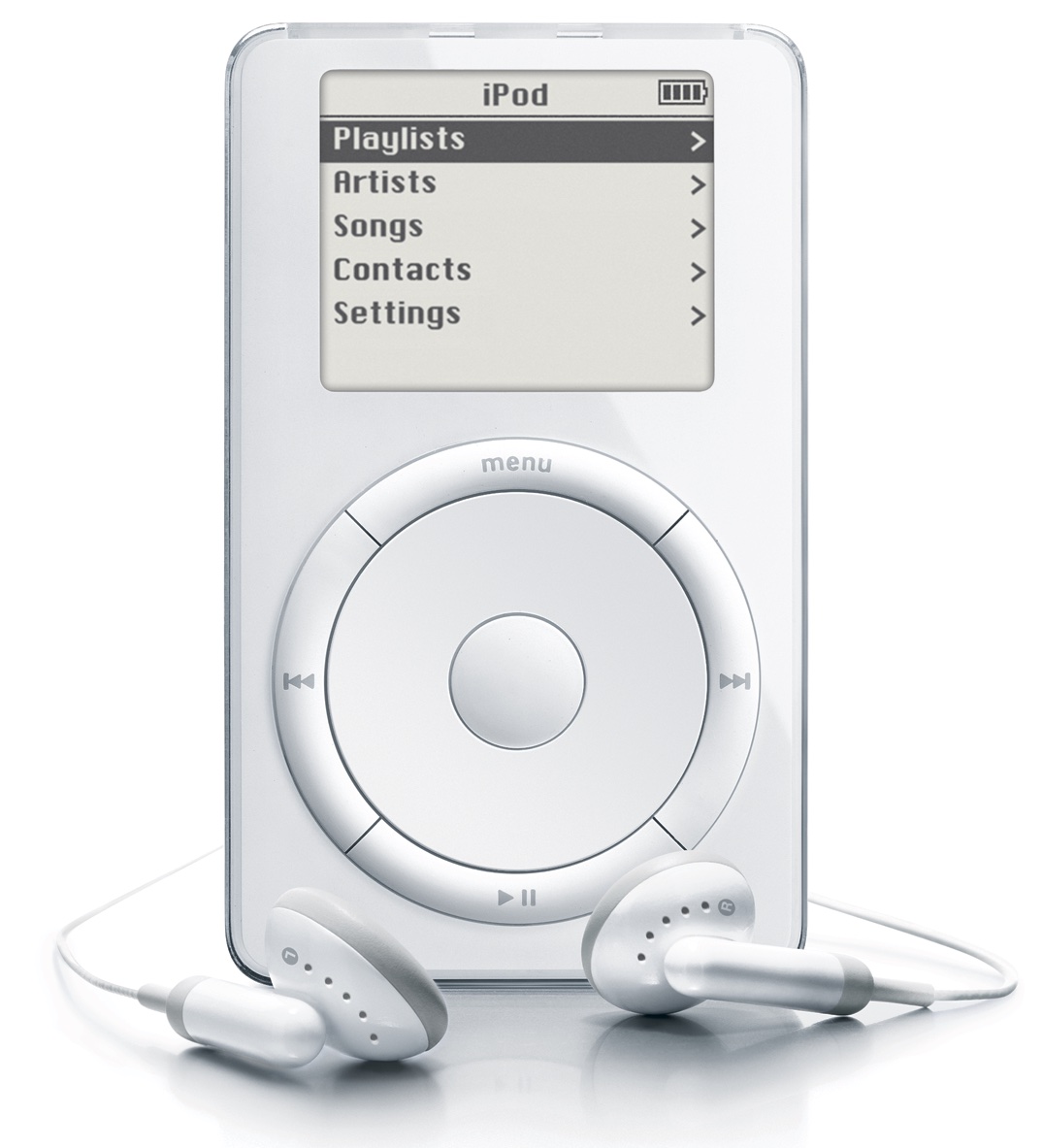

2. Digitisation of music: the modulation of analogue music into digital signals enabled a variety of simplifications (and thus cost savings) on the production side, but also lossless copying and reproduction options on the consumption side, which plunged music providers into a profound crisis, the consequences of which they are still suffering from today. The killer application for classic physical music carriers came from Apple in 2001. The iPod combined the mobility of the Walkman with the advantages of sound quality and user-friendliness of digital music storage (Fig. 35):

Fig. 35 – Apple iPod, 2001

3. Cheep internet bandwidth: From the turn of the millennium, the internet developed into a global network and enabled not only the omnipresent availability of music, but also the quick and inexpensive transfer of (music) files.

4. Return to visuality: Historically, cultural consumption has always been a primarily visual experience – even in opera and concerts. With the development of sound reproduction devices for domestic use, a large part of music consumption shifted to a purely auditory experience. As a result of ever-increasing and cheaper internet bandwidth, high-quality videos are available everywhere and at all times, so that music is increasingly being consumed in a combination of video and audio rather than purely audibly.

5. Emergence of gigantic online music libraries: From the turn of the millennium, gigantic music archives became increasingly available at low cost (streaming services at EUR 9.90 per month for 100 million tracks or free of charge via YouTube). This has dramatically simplified access to music and made it dependent on online access.

In parallel to these technical changes, people’s social lifestyles and behaviour were also changing:

1. Changing living and, above all, working conditions are blurring the boundaries between work and private life, so that there is no longer a clear separation between work and leisure behaviour. As a result, many people parallelise their activities and, for example, no longer consume music in separate free time periods at home, but on the way to/from work or during work or during other activities, such as sport or housework.

2. Cheap internet bandwidth promotes people’s permanent online networking and interaction, both in their work and leisure behaviour, with the result that all relevant social behaviour becomes online behaviour, respectively whatever cannot be networked online drastically loses interest and importance.

3. Personalisation and individualisation of all online behaviour – including music and its players. Online algorithms seek to learn to know the users and their tastes, producing a never ending list of further suggestions, tailored specifically for them.

4. Freemium mentality of the internet generation, respectively renting instead of owning. The younger generations socialised by the Internet are used to getting something seemingly for free. The expectations towards providers of music hardware and software have changed accordingly. Modern pricing models often include a low-cost or even free upfront service, combined with a subscription model with a minimum time commitment (e.g. mobile telephony, TV streaming, etc.).

5. Until the end of the 20th century, the stereo system at home was a perfect social status symbol, like the employer, the colour TV or the car in front oft he house. Until the end of the century, people in the western world demonstrated their social status essentially by displaying their material assets and their immaterial contemporaneity, i.e. their affinity for and mastery of technology. The ostentatious display of material wealth – at least of everyday objects (like a fridge, mobile phone, TV, stereo, car, etc.) – as a signal of one’s social status has declined significantly. A villa or a yacht is of course still a strong status symbol, but objects of daily use are no longer. With the rise in the general standard of living, everyone has more or less the same utensils for everyday use. These days, you can no longer impress anyone with having a fridge or a TV set – or for that matter with a stereo. Since the 21st century, particularly young consumers have been proving their status primarily through their online behaviour and mastery of technology. In the 21st century, self-documentation and online networking offer much greater status potential than any hardware in the living room, which hardly anyone ever gets to see. Especially as the online behaviour also provides a much more immediate confirmation of status than any objects in one’s own home.

With the combination of these five technological and five socio-economic developments, the way people consume music shifted so drastically that the established hifi manufacturers could no longer keep up:

1. Music is available in file format and thus detached from specific data carriers (tape, record, CD)

2. Video has become an important part of music consumption

3. So far, the requirements for music playback devices primarily consisted of: Sound quality, design and user-friendliness. Through the above mentioned technical and socio-economic changes, this has now changed to accessibility, portability and convenience.

4. Digitalisation and technical progress have dramatically improved the sound quality of even relatively simple music playback devices over the last 40 years. It may now have reached a point where, for the majority of people, large high-end audio components no longer offer any comprehensible added value.

5. Consequently, serious hifi devices no longer have a place in the mainstream of modern music consumption. Justifying their necessity with sound quality arguments is therefore no longer valid. The devices required for listening to music are sufficiently represented by networked mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets. At most, the Bluetooth or WLAN-enabled loudspeaker, which is fully integrated into the current living environment to the point of invisibility, is still accepted.

6. Todays music collections (consisting of favourites and playlists on streaming services or files one owns on cloud storage) are stored somewhere on the World Wide Web and should be accessible on all end-devices at any time in a similar way: on the hi-fi system in the living room, the small audio system in the study, but also on the all-in-one system in the bathroom and the clock radio in the bedroom and, of course, on all smartphones and tablets as well as in the car entertainment system. However, hardware manufacturers could only deliver this if they were full-range suppliers of networked consumer electronics or entered into co-operations with corresponding companies, i.e. if they produced kitchen radios, car radios, televisions and smartphones etc. in addition to hi-fi devices.

7. Young people have been an important driving force behind the development of the hi-fi industry since the 1950s. Since the turn of the millennium, young people have largely said goodbye to hi-fi. When it comes to music consumption, they have other priorities than high-quality audio devices:

- ‘Coolness factor’ of the latest mobile devices

- Not only listening to music, but also watching it

- Networking and sharing their music consumption with friends (of which every teenager these days has at least a few thousand)

- Unlimited choice and availability of music, preferably for free

- Music consumption is less concentrated listening (where audio quality would play a role), but more background music for other activities (where audio quality does not play a major role)

8. Music has mutated from a cultural asset that was treated with the appropriate respect to a lifestyle accessory, like a room fragrance spray that is used to create the respective mood and atmosphere – which is mainly consumed on the side, during other activities. According to a study by the University of Hamburg on the ‘Future of music consumption’ in 2018, music is nowadays only actively consumed while doing housework and driving the car. The question of when people consume music in a focussed and exclusive manner was not even asked anymore.

9. All in all, music is these days generally available – everywhere, at any time in huge archives (including videos) at low cost and in good quality. The music can be played back in acceptable quality on relatively cheap playback devices (compared to classic hi-fi devices, e.g. smartphones, computers or notebooks). The only prerequisite for enjoying it is online connection.

As a result, the culture of listening to music has changed since 1900 – from a more or less concentrated, self-determined, purely auditory consumption of selected pieces of music during conscious relaxation times to a primarily mobile background noise floor for other activities through increasingly externally determined, algorithms-controlled playlists.

Fig. 36 – Mobile music consumption in the 21st c. during sport

Basically, these developments have massively devalued music itself and the devices used to play it. As a result, listening to music itself has also been devalued. In particular, music consumption has become dependent on the online world with its specific values and social behaviours. In a way, this is the price that the music industry is paying for the fact that the major record labels have been able to repair their sales and distribution model, in the wake of the digital revolution, which they themselves initiated in the early 1980ies.

This development is undoubtedly not to the detriment of customers, who can access more high-quality music more easily and more cheaply than ever before. On the one hand, the development is a cultural-historical problem due to the devaluation of music listening and, on the other, a problem for the manufacturers of classic hi-fi equipment. Following the disappearance of the major classical manufacturers, the manufacturing landscape has now drifted apart:

- On the one hand, there are a large number of small manufacturers (with annual sales of less than EUR 10 million) that focus on an exclusive audiophile clientele with sometimes extremely high-priced high-end products, but are still struggling to survive economically due to their cost structure and can only be kept going by a great deal of personal passion on the part of the founders/owners. Consolidation is unavoidable here. Financial investors such as the FineSounds Group (now renamed ‘McIntosh Group’) have recognised this and consolidated some of the largest hi-fi brands such as Sonus Faber, McIntosh, Audio Research, Wadia etc.

- And on the other hand, the big internet companies, such as Apple, Google and Amazon or even Sonos, which focus on the masses of less audiophile, less demanding lifestyle people and make highly profitable business here with comparatively cheap devices.

The middle ground has disappeared with the big traditional hi-fi manufacturers.

Outlook

The next round in the evolution of the culture of music listening is already under way:

Music – available always and everywhere – with ever simpler operation, has been a key driver of change in the culture of music listening from the very beginning. However, this is now taking on completely new dimensions:

- We have just become accustomed to new forms of music consumption at the computer or smartphone through streaming with its link- and algorithm-controlled ‘stream of musical consciousness’. The stream knows interruptions – the constant clicking of the next button – but it knows no pauses. When one song ends, the algorithm brings up the next. An analysis of the world’s leading music markets by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) in 2018 found, among other things, that

– respondents spend an average of 17.8 hours/week listening to music. That is more than ever before

– 86% of all listeners access this music via streaming services – most of the time is spent on YouTube (47%).

We are littering ourselves with music. Within 100 years, a luxury good has finally become an almost worthless mass product that is as available as air. Cultural pessimists worry not without reason.

- And the next development step is already underway: music via voice control further simplifies operation (Fig. 37): ‘Alexa, play for me …’

Fig. 37 – Amazon Alexa, 2017

- We no longer even have to choose the music ourselves. Self-learning AI algorithms do this for us based on our current mood – determined by facial scanning – and the knowledge of our musical tastes acquired over time. ‘Alexa, play me something relaxing …’. The music never stops. And as our taste in music increasingly develops in response to the algorithms’ suggestions, at some point the question arises as to what our taste in music can actually consist of.

- Singles and albums no longer play the role they did previously. Instead, the playlist dominates today. In the 70s and 80s, young people still sat in front of the radio and put together their mix tapes from hit parade programmes. And woe betide you if the presenter chatted into the song. Today, music consumption means listening to flat-rate playlists that are either put together by the listener or provided by streaming services. While music fans used to exchange records, cassettes or CDs, today they create their own playlists online and share them with friends. Meanwhile, streaming services market playlists as the main platform for music and fans subscribe to them according to their musical tastes. For example, in Germany, Spotify’s ‘Modus Mio’ (German rap) is one of the most streamed playlists with 750,000 subscribers). Spotify even organises concerts of its leading playlists (Modus Mio Live on stages in Berlin and Dortmund, 2018). In other words, it is no longer the artist who is at the centre of the concert and fan interest, but the playlist. So it’s no longer so surprising that Spotify also offers merchandising for its playlists, just like the record labels used to do for an artist (Modus Mio T-shirt, Modus Mio hoodie, Modus Mio coffee mug, etc.) – Seriously?!

- So far, the winners of this development have been the superstars and the major labels, who have made significant revenues from streaming. It has not been possible to establish a fair streaming service. Comparatively artist-friendly offerings such as Deezer have not been able to establish themselves; sympathetic roots platforms such as Bandcamp offer an alternative, but have not developed a streaming service with the functions of Spotify or YouTube. Instead, Spotify has become the all-dominant pop discounter that trades more in our personal data than in music.

- Many artists are asking themselves where the money ends up that the music industry is now at last earning again after the previous decade of crisis. After all, the amounts received by artists per stream are a pittance (according to Digital Music News, the most recent averages were a rounded 0.007 euros/stream for Apple Music, 0.004 euros for Spotify and 0.0006 euros for YouTube. With 50,000 downloads, an artist would therefore earn about 350 euros (Apple), 200 euros (Spotify) and 30 euros (YouTube). In the case of a download or a CD single, on the other hand, between 13 and 20 per cent of the sales price is or was received by the artist – 50,000 downloads would therefore be 6,500 euros upwards.

- Aesthetically, the clickocracy in the music business has a massive impact. Songs are already being composed to Spotify standards. Spotify counts a track as being played only once it has exceeded the 30-second mark. So the first 30 seconds have to really pop. At the beginning of the track, decisive motifs must already appear. The customer must be triggered. Whereas conventional mainstream mass production used to be based on radio airplay, it is now based on streaming demands.

- … and since software algorithms now know better what we want to hear than we do ourselves, why not have AI systems compose and produce the music in the first place? The company AIVA (‘The Artificial Intelligence composing emotional soundtrack music’) offers composition services on the Internet. For EUR 14/month, you can have AVIVA compose as much music as you want – and download all royalty-free. Much of the ambient music we hear in cafés, department stores or clubs is now created by computers. An algorithm has completed Franz Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony on a Mate 20 Pro smartphone from Huawei and Huawei gave the world premiere of the work on 6 February 2019 in the historic Cadogan Hall in London with the 66-piece English Session Orchestra. … There’s still a lot in store for us music listeners …

- In reality, progress in the development of sound quality on the hardware side is declining in the mass market. Most people today use Bluetooth speakers and soundbars (which accounted for over 90% of speakers sold in 2018) to listen to dynamically-compressed music in mono. The last time that happened was 70 years ago.

My personal assessment: what has been lost in the course of digitalisation and the increasingly easy and mass availability of music is the personal relationship to music and consequently also to the devices that play it. Music producer Rick Beato talks about how, as a teenager, he took on jobs during his summer holidays so that he could buy certain albums. As soon as he owned the albums, he listened to them intensively, studied their cover art and memorised their lyrics. Beato’s point is that he used to have to pay a high price for his few music albums and therefore valued them accordingly. That’s simply completely different today. Whether you like it or not, the general availability – which also means the democratisation – of anything leads to its inevitable devaluation. Today, music is available in huge quantities practically free of charge – Tidal, Spotify & Co. make 100 million tracks available with the swipe of an index finger – at EUR 9.90 a month. Thousands of new albums are released every month – the digitalisation of music production has also meant that practically anyone can now produce their own music with relatively little effort and put it online (Soundcloud, Bandcamp). In this mass of offers, people have completely lost orientation and therefore no longer have a chance to build a personal relationship with ‘their’ music (tyranny of choice). If 28-year-olds today own music collections with 20,000 albums, what relationship can a twenty-something still have to individual albums? Streaming providers are endeavouring to counteract the selection problem with curated offerings – with rather modest success.

Music has indeed degenerated from a cultural asset to an almost worthless stream of background noise, as a soundtrack to the staging of peoples lifes, to which they can pay little conscious attention – if only because of sensory overload. But that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Even before the 20th century, few people were able to engage with culture in general and music in particular. Basically, they do just as little today. But because music is so cheaply available nowadays and because it has the unique ability to transport emotions immediately, it is often used to decorate everyday life. And why not? This has the not insignificant advantage that for those who are actually interested in music, the choice has never been greater.

I could imagine that the Hegelian dialectic will soon set in with a counter-movement that will once again draw more conscious attention to listening to music and the quality of sound. This has happened with the consumption of e.g. literature or even food over the last 30 years. The central element of listening to music is and remains the emotional experience. The emotionality of music can hardly be experienced en passant and from plastic devices. The vinyl boom is probably just the first indication of this.

© Alexej C. Ogorek

Sources:

- Bayley (Hrsg.), Amanda, Recorded Music: Performance, Culture and Technology, (Cambridge University Press) Cambridge, New York 2009

- Blake, Andrew, To the Millennium: Music as Twentieth-Century Commodity, in: N. Cook u. A. Pople (Hrsg.), The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Music, (Cambridge University Press) Cambridge 2004

- Prof. Dr. Michel Clement, Universität Hamburg: Studie zur Zukunft der Musiknutzung, 2018

- P. Wicke – Musikproduktion als Interpretation, 2010

- Gideon Schwartz: Hi-Fi, Phaidon, 2019

- H.A. Hartley: Audio Design Handbook, Gernsback Library, 1958

- Schmidt Horning, Susan Engineering the Performance: Recording Engineers, Tacit Knowledge and the Art of Controlling Sound, in: Social Studies of Science, 34 (2004)

- Car History (www.carhistory4u.com/the-last-100-years/parts-of-the-car/car-radio)

- HiFi-Geräte Werbeanzeigen (www.audiokarma.org/forums/index.php?threads/interesting-stereo-ads-post-a-pic-for-memory-lanes-sake.567692)

- Rick Beato: The Real Reason Why Music Is Getting Worse